Archived information

Archived information is provided for reference, research or recordkeeping purposes. It is not subject to the Government of Canada Web Standards and has not been altered or updated since it was archived. Please contact us to request a format other than those available.

Chapter 5.2 - Fiscal Outlook

The Government is committed to a transparent and objective budget planning process. To achieve this, the economic forecast underlying the Government’s fiscal projections is based on an average of private sector economic forecasts. This process has been followed for over two decades and has been endorsed by the International Monetary Fund. Economic Action Plan 2015 maintains that approach.

As described in Chapter 2, although the March 2015 private sector survey is considered to be a reasonable basis for fiscal planning purposes, the global economic outlook remains uncertain. As a result, the Government has judged it appropriate to maintain a downward adjustment for risk to the private sector forecast for nominal gross domestic product (GDP) over the 2015–16 to 2019–20 period. This downward adjustment for risk translates to a set-aside for contingencies of $1.0 billion per year between 2015–16 and 2017–18, $2.0 billion in 2018–19 and $3.0 billion in 2019–20, which, for fiscal planning purposes, is applied proportionally against projected revenues.

As discussed in Chapter 5.1, the set-aside for contingencies will be used, if not required, to reduce the federal debt. This will help ensure that the federal debt-to-GDP ratio remains on a downward path.

| 2015– 2016 | 2016– 2017 | 2017– 2018 | 2018– 2019 | 2019– 2020 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Set-aside for contingencies | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 3.0 |

Fiscal Outlook Before the Measures Announced in Economic Action Plan 2015

More than five years after the global recession, the Government’s track record of sound fiscal management has paid off for Canadians, resulting in budgetary surpluses starting this year.

However, Canada is not immune to external developments. As described in Chapter 2, projections for nominal GDP—the broadest single measure of the tax base—have been revised down compared to the November 2014 Update of Economic and Fiscal Projections (Fall Update), largely reflecting the economic impact of lower crude oil prices.

These economic developments, together with fiscal developments since the Fall Update, have led to a downward adjustment to the fiscal outlook, as lower projected budgetary revenues have not been fully offset by lower projected program expenses and public debt charges in most years.

A summary of the changes in the fiscal projections between the Fall Update and Economic Action Plan 2015 is provided in Table 5.2.2.

| Projection | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2013– 2014 | 2014– 2015 | 2015– 2016 | 2016– 2017 | 2017– 2018 | 2018– 2019 | 2019– 2020 | |

| 2014 Fall Update budgetary balance |

-5.2 | -2.9 | 1.9 | 4.3 | 5.1 | 6.8 | 13.1 |

| Add: Set-aside for contingencies in Fall Update | 3.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 | |

| 2014 Fall Update budgetary balance before set-aside for contingencies | -5.2 | 0.1 | 4.9 | 7.3 | 8.1 | 9.8 | 16.1 |

| Impact of economic and fiscal developments1 |

|||||||

| Budgetary revenues | -1.3 | -6.0 | -7.1 | -6.4 | -6.4 | -6.5 | |

| Program expenses | |||||||

| Major transfers to persons | 0.3 | 0.8 | 0.9 | 1.1 | 1.2 | 1.4 | |

| Major transfers to other levels of government | -0.2 | -0.1 | 0.1 | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.3 | |

| Direct program expenses | -0.4 | 0.2 | -1.4 | -1.5 | -0.2 | -1.8 | |

| Total | -0.3 | 0.9 | -0.3 | 0.0 | 1.3 | -0.1 | |

| Public debt charges | 1.0 | 3.0 | 4.0 | 4.2 | 3.4 | 3.1 | |

| Total economic and fiscal developments |

-0.5 | -2.1 | -3.4 | -2.1 | -1.8 | -3.6 | |

| Less: Set-aside for contingencies in Economic Action Plan 2015 | -1.0 | -1.0 | -1.0 | -2.0 | -3.0 | ||

| Revised status quo budgetary balance (before budget measures) | -5.2 | -0.4 | 1.8 | 2.9 | 5.0 | 6.0 | 9.5 |

Compared to the Fall Update, projected budgetary revenues are lower over the forecast horizon. This decline is primarily due to lower projections for tax revenues driven by weaker-than-expected year-to-date results and the lower forecast for nominal GDP. Budgetary revenues are also negatively affected by a lower expected rate of return on interest-bearing assets—recorded as part of other revenues—as a result of a lower forecast for interest rates.

The projected decrease in budgetary revenues is offset to a small extent by the proceeds from asset sales and increases in projected flow-through revenues, such as consolidated Crown corporation revenues, over the forecast horizon. Flow-through revenues, however, give rise to an equal and offsetting reduction in total expenses with no impact on the budgetary balance.

Impact of Proceeds From Asset Sales on the Budgetary Balance billions of dollars

| Projection | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2014–15 | 2015–16 | 2016–17 | 2017–18 | 2018–19 | 2019–20 | |

| Proceeds from asset sales since the Fall Update | 0.9 | 2.2 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| Provision for asset sales in the Fall Update |

0.2 | 1.2 | ||||

| Impact on budgetary balance | 0.6 | 1.0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

A provision of $0.2 billion in 2014–15 and $1.2 billion in 2015–16 was included in the 2014 Fall Update to account for projected asset sales, consistent with transparent accounting and fiscal planning.

Three sales of government assets have occurred since:

- A fiscal gain of $0.9 billion was realized on the transfer to Ontario of the Province’s one-third portion of the Government’s holdings of General Motors (GM) common shares, following a request by the Province for transfer of the shares.

- The Government completed an auction of AWS-3 spectrum licences in March 2015, which raised a total of $2.1 billion. Consistent with public sector accounting standards, the revenues from this auction will be recognized evenly over the 20-year term of the licences.

- The Government divested its remaining GM shares on April 6, 2015, for gross sale proceeds of C$3.3 billion. After deducting the book value of the shares, the net gain is C$2.1 billion.

In total, net of the asset sale provision, proceeds from asset sales since the Fall Update contribute $0.6 billion to the budgetary balance in 2014–15, $1.0 billion in 2015–16 and $0.1 billion per year between 2016–17 and 2019–20. This contribution is recorded as an increase in budgetary revenues since the Fall Update.

Overall, expenses are expected to be lower than the level projected in the Fall Update over the forecast horizon, with an increase in direct program spending being more than offset by lower projected major transfers to persons and public debt charges.

Major transfers to persons are projected to be lower due to lower expected inflation and year-to-date results, as well as revised estimates of the projected number of recipients for elderly benefits.

Major transfers to other levels of government are broadly unchanged from the Fall Update in the near term. However, they are expected to be lower in the outer years due to a lower forecast for nominal GDP.

Direct program expenses are expected to be higher than projected in the Fall Update in most years, as a result of:

- Higher projected public service pension and benefit expenses, reflecting lower projected long-term interest rates since the Fall Update, as long-term interest rates are used in the valuations of the Government’s liabilities for employee pensions and other future benefits. While the total pension and benefit obligation of the Government has not changed, lower projected interest rates result in relatively more of these costs being recognized in the near term rather than the future.

- Higher projected expenses for the Canadian Commercial Corporation, reflecting new contracts signed with respect to Canadian defence exports. However, as the corporation is fully consolidated in the Government’s financial statements, expenses for the corporation are flow-through expenses, which give rise to an equal and offsetting increase in total revenues with no impact on the budgetary balance.

The outlook for direct program expenses has also been revised to reflect the Government’s actions to improve fiscal management and planning. Based on recent departmental spending trends, the estimated lapse of departmental spending included in the fiscal projection has been revised upwards though it is still lower than the average lapse over the last decade.

The lapse included in the fiscal projections reflects an estimate of planned spending that does not proceed in any given year. Lapses in departmental spending are to be expected, as they result from factors such as lower-than-expected costs for programming and revised schedules for implementation of initiatives. Lapses reflect the Government’s commitment to the responsible use of public funds—funds are only spent when necessary.

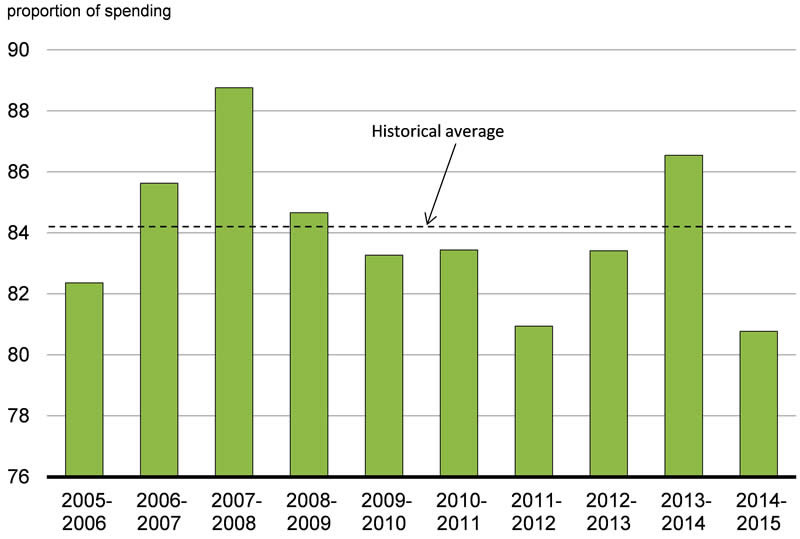

Year-to-date results for 2014–15 indicate that lapses in departmental spending will be higher than anticipated in the Fall Update. Year-to-date spending for the April 2014 to February 2015 period is significantly lower than spending during this same period in previous years. In fact, the proportion of spending incurred over this period for 2014–15 is well below the historical average of 84.3 per cent (Chart 5.2.1). Moreover, year-to-date spending results for 2014–15 are at the lowest level in a decade.

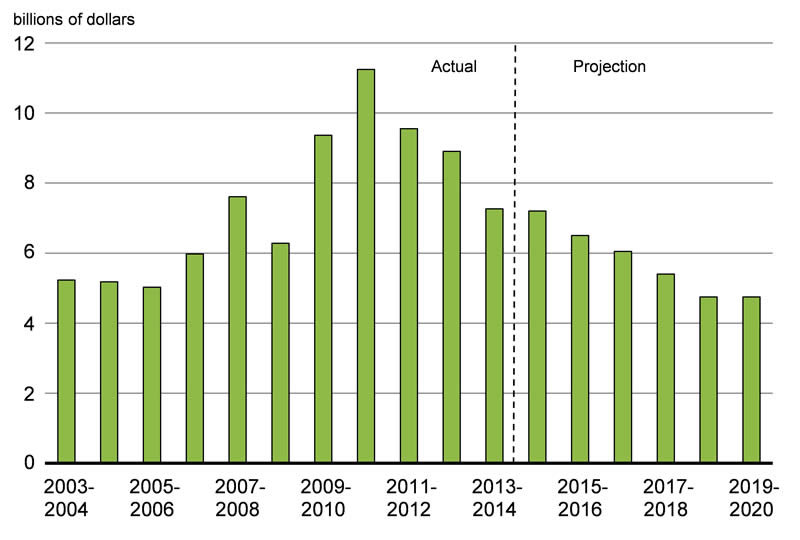

In recognition of the low year-to-date spending results, the forecasted lapse has been revised upwards by $1.0 billion in 2014–15. To be prudent, gradually smaller upward revisions have been made for 2015–16, 2016–17 and 2017–18. No upward revision is made in 2018–19, when the lapse amount is projected to be about $4.8 billion (Chart 5.2.2). As a proportion of appropriations, the lapse is projected to be about 5 per cent by 2018–19, which is close to post-2000 historical lows. The assumption that the lapse trends towards post-2000 historical lows introduces an element of prudence into the fiscal projections.

The total budgetary lapse for 2012–13, as presented in the 2013 Public Accounts of Canada, is $10.1 billion; however, $1.2 billion of this lapse corresponds to frozen allotments applied to departmental appropriations to implement Budget 2012 reductions to departmental spending. Consequently, the effective lapse in departmental spending for 2012–13 is $8.9 billion.

Sources: Public Accounts of Canada; Department of Finance.

Public debt charges are expected to be lower than projected in the Fall Update over the forecast horizon. In 2014–15, this is largely due to lower-than-expected Consumer Price Index adjustments on Real Return Bonds. In 2015–16 and future years, public debt charges are lower than previously projected due to lower forecast interest rates.

Fiscal Impact of the Measures in Economic Action Plan 2015

Table 5.2.3 sets out the impact of the measures introduced in Economic Action Plan 2015.

| Projection | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2014– 2015 | 2015– 2016 | 2016– 2017 | 2017– 2018 | 2018– 2019 | 2019– 2020 | |

| Revised status quo budgetary balance (before budget measures) | -0.4 | 1.8 | 2.9 | 5.0 | 6.0 | 9.5 |

| Budget measures1,2 | ||||||

| Creating Jobs and Economic Growth | 0.0 | -0.4 | -1.0 | -1.8 | -2.5 | -3.4 |

| Ensuring a Healthier and More Productive Public Service | 0.9 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.1 | |

| Prosperous Families and Strong, Secure Communities | -1.6 | -1.0 | -0.9 | -1.2 | -1.4 | -1.7 |

| Improving the Fairness and Integrity of the Tax System and Strengthening Tax Compliance | 0.0 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 0.4 | |

| Total budget measures | -1.6 | -0.5 | -1.2 | -2.4 | -3.4 | -4.7 |

| Budgetary balance (after budget measures) |

-2.0 | 1.4 | 1.7 | 2.6 | 2.6 | 4.8 |

As discussed in Chapter 3, Economic Action Plan 2015 is investing $9.2 billion over six years to support job creation and promote economic growth. These investments build on the Government’s plan for jobs and growth by supporting the manufacturing sector and advanced research, helping small businesses and entrepreneurs create jobs, helping train a highly skilled workforce, investing in infrastructure, and growing trade and expanding markets.

The expenditure outlook presented in this budget incorporates the estimated fiscal impact of the modernization of the disability and sick leave management system, based on the Government’s latest proposal to federal public service bargaining agents. As required under public sector accounting standards, the Government’s liability associated with accumulated sick leave entitlements will be re-evaluated in light of final improvements to the system.

In addition, Economic Action Plan 2015 builds on the Government’s record of support for Canadian families and communities. As discussed in Chapter 4, the Government is continuing to provide tax relief for Canadian families, providing support to seniors and caregivers, and taking action to help build strong communities, celebrate and protect Canada’s natural and cultural heritage and better protect Canadians. The Government is also taking action for veterans to enhance benefits for severely disabled veterans, provide fair treatment to part-time Reserve Force veterans and increase support for family caregivers. All told, actions to ensure prosperous families and strong, secure communities, including support for veterans, will deliver $7.8 billion in tax relief, benefits and new investments over six years.

Lastly, as discussed in Chapter 5.1, Economic Action Plan 2015 proposes a number of new measures as part of the Government’s ongoing effort to improve the fairness and integrity of the tax system and strengthen tax compliance. These proposed measures will improve the budgetary balance by $1.9 billion over five years.

Summary Statement of Transactions

Table 5.2.4 summarizes the Government’s financial position over the forecast horizon. These projections are based on the average private sector forecast for the economy described in Chapter 2, and the set-aside for contingencies discussed previously.

| Projection | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2013– 2014 | 2014– 2015 | 2015– 2016 | 2016– 2017 | 2017– 2018 | 2018– 2019 | 2019– 2020 | |

| Budgetary revenues | 271.7 | 279.3 | 290.3 | 302.4 | 313.3 | 326.1 | 339.6 |

| Program expenses | 248.6 | 254.6 | 263.2 | 274.3 | 282.7 | 293.0 | 302.6 |

| Public debt charges | 28.2 | 26.7 | 25.7 | 26.4 | 28.0 | 30.5 | 32.1 |

| Total expenses | 276.9 | 281.3 | 288.9 | 300.7 | 310.7 | 323.5 | 334.7 |

| Budgetary balance | -5.2 | -2.0 | 1.4 | 1.7 | 2.6 | 2.6 | 4.8 |

| Financial position | |||||||

| Total liabilities | 1,000.8 | 1,015.5 | 1,030.3 | 1,041.8 | 1,055.0 | 1,064.5 | 1,073.9 |

| Total financial assets1 | 318.5 | 326.9 | 338.3 | 348.4 | 362.2 | 372.6 | 385.2 |

| Net debt | 682.3 | 688.6 | 692.0 | 693.4 | 692.7 | 691.9 | 688.7 |

| Non-financial assets | 70.4 | 72.6 | 75.0 | 78.1 | 80.1 | 81.8 | 83.5 |

| Federal debt | 611.9 | 616.0 | 617.0 | 615.3 | 612.6 | 610.1 | 605.2 |

| Per cent of GDP | |||||||

| Budgetary revenues | 14.3 | 14.1 | 14.5 | 14.4 | 14.3 | 14.3 | 14.3 |

| Program expenses | 13.1 | 12.9 | 13.2 | 13.1 | 12.9 | 12.8 | 12.7 |

| Public debt charges | 1.5 | 1.4 | 1.3 | 1.3 | 1.3 | 1.3 | 1.4 |

| Budgetary balance | -0.3 | -0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.2 |

| Federal debt | 32.3 | 31.2 | 30.8 | 29.3 | 27.9 | 26.7 | 25.5 |

As a result of the Government’s responsible management of public finances and after accounting for the measures announced in Economic Action Plan 2015, a surplus of $1.4 billion is projected for 2015–16. The surplus is projected to grow to $4.8 billion in 2019–20.

The federal debt-to-GDP ratio (accumulated deficit) fell to 32.3 per cent in 2013–14. The debt-to-GDP ratio is expected to fall to 25.5 per cent by 2019–20, putting the Government well on its way to meeting its commitments to reduce the debt-to-GDP ratio to pre-recession levels by 2017 and to 25 per cent of GDP by 2021. Lower debt levels also mean lower debt-servicing costs, which results in lower taxes for Canadians and a strong investment climate that supports job creation and economic growth.

The expected reduction in federal debt will help to ensure that Canada’s total government net debt (which includes that of the federal, provincial/territorial and local governments as well as the net assets of the Canada Pension Plan and the Québec Pension Plan) will remain the lowest, by far, of any Group of Seven (G-7) country and among the lowest of the advanced G-20 countries.

Outlook for Budgetary Revenues

| Projection | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2013– 2014 | 2014– 2015 | 2015– 2016 | 2016– 2017 | 2017– 2018 | 2018– 2019 | 2019– 2020 | |

| Income taxes | |||||||

| Personal income tax | 130.8 | 134.2 | 143.4 | 151.8 | 159.3 | 165.9 | 172.9 |

| Corporate income tax | 36.6 | 37.9 | 36.8 | 39.5 | 40.4 | 40.9 | 42.5 |

| Non-resident income tax | 6.4 | 6.4 | 6.2 | 6.5 | 6.9 | 7.3 | 7.7 |

| Total income tax | 173.8 | 178.5 | 186.4 | 197.8 | 206.6 | 214.1 | 223.0 |

| Excise taxes/duties | |||||||

| Goods and Services Tax | 31.0 | 31.5 | 32.7 | 34.6 | 36.5 | 38.0 | 39.5 |

| Customs import duties | 4.2 | 4.5 | 4.9 | 5.0 | 4.7 | 4.9 | 5.1 |

| Other excise taxes/duties | 10.9 | 11.4 | 11.4 | 11.4 | 11.4 | 11.4 | 11.3 |

| Total excise taxes/duties | 46.1 | 47.4 | 49.0 | 50.9 | 52.6 | 54.3 | 55.9 |

| Total tax revenues | 219.9 | 225.9 | 235.4 | 248.8 | 259.2 | 268.4 | 279.0 |

| Employment Insurance premium revenues | 21.8 | 22.6 | 23.1 | 22.5 | 19.8 | 20.6 | 21.4 |

| Other revenues | 30.0 | 30.9 | 31.7 | 31.2 | 34.4 | 37.2 | 39.2 |

| Total budgetary revenues | 271.7 | 279.3 | 290.3 | 302.4 | 313.3 | 326.1 | 339.6 |

| Per cent of GDP | |||||||

| Personal income tax | 6.9 | 6.8 | 7.2 | 7.2 | 7.2 | 7.3 | 7.3 |

| Corporate income tax | 1.9 | 1.9 | 1.8 | 1.9 | 1.8 | 1.8 | 1.8 |

| Goods and Services Tax | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.7 | 1.7 | 1.7 |

| Total tax revenues | 11.6 | 11.4 | 11.8 | 11.9 | 11.8 | 11.7 | 11.7 |

| Employment Insurance premium revenues | 1.1 | 1.1 | 1.2 | 1.1 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.9 |

| Other revenues | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.5 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.7 |

| Total budgetary revenues | 14.3 | 14.1 | 14.5 | 14.4 | 14.3 | 14.3 | 14.3 |

Table 5.2.5 sets out the Government’s projection for budgetary revenues after factoring in the set-aside for contingencies, and reflecting Economic Action Plan 2015 measures. For planning purposes, the set-aside for contingencies is applied proportionally to tax revenues and other revenues, excluding flow-through revenues.

Overall, budgetary revenues are expected to increase by 2.8 per cent in 2014–15 based on year-to-date fiscal results and recent economic developments. Over the remainder of the forecast horizon, revenues are projected to grow at an average annual rate of 4.0 per cent, roughly in line with growth in nominal GDP.

Personal income tax revenues—the largest component of budgetary revenues—are projected to increase by $3.4 billion, or 2.6 per cent, to $134.2 billion in 2014–15. This reflects the tax relief measures for families announced in the fall of 2014, notably the Family Tax Cut. Over the remainder of the projection period, personal income tax revenues are forecast to increase somewhat faster than growth in nominal GDP, averaging 5.2 per cent annual growth, reflecting the progressive nature of the income tax system combined with projected real income gains.

Corporate income tax revenues are projected to increase by $1.3 billion, or 3.7 per cent, to $37.9 billion in 2014–15. In 2015–16, corporate income tax revenues are projected to decline by 2.9 per cent, reflecting the expected impact of lower oil prices. Over the remainder of the projection period (in 2016–17 and beyond), corporate income tax revenues are forecast to grow at an average annual rate of 3.6 per cent, reflecting the projected recovery in oil prices and growth in corporate profits.

Non-resident income tax revenues are income taxes paid by non-residents of Canada on Canadian-sourced income, notably dividends and interest payments. For 2014–15, non-resident income tax revenues are projected to remain at the same level as in 2013–14 ($6.4 billion), as they were temporarily increased by one-time factors in 2013–14. Over the remainder of the forecast horizon, non-resident income tax revenues are projected to increase at an average annual rate of 3.9 per cent.

Goods and Services Tax (GST) revenues are forecast to grow by 1.5 per cent in 2014–15 based on projected growth in taxable consumption and year-to-date results. Over the remainder of the projection period, GST revenues are forecast to grow by 4.7 per cent per year on average, based on projected growth in taxable consumption and in the GST/HST Credit.

Customs import duties are projected to increase by 5.9 per cent in 2014–15, reflecting year-to-date results and projected growth in imports. Over the remainder of the projection period, there is some volatility in the annual growth in customs import duties, reflecting, in part, the expected impacts of the Canada-European Union Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement and the Canada-Korea Free Trade Agreement.

Other excise taxes and duties are projected to increase by 4.7 per cent in 2014–15, reflecting year-to-date results, and are expected to remain stable over the remainder of the projection period.

Employment Insurance (EI) premium revenues are projected to grow by 3.6 per cent in 2014–15 and by 2.5 per cent in 2015–16, reflecting the growth in insurable earnings, as well as the offsetting impact of the Small Business Job Credit. Following the introduction of the seven-year break-even rate mechanism in 2017, EI premium rates are expected to decrease from $1.88 in 2016 to an estimated $1.49 in 2017, a reduction of 21 per cent, which has the effect of significantly reducing projected premium revenues in 2016–17 and 2017–18. EI premium revenues are expected to return to an upward trend in 2018–19 onwards.

| 2014– 2015 | 2015– 2016 | 2016– 2017 | 2017– 2018 | 2018– 2019 | 2019– 2020 | (…) | 2023– 2024 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EI premium revenues | 22.6 | 23.1 | 22.5 | 19.8 | 20.6 | 21.4 | ||

| EI benefits1 | 17.8 | 18.4 | 19.0 | 19.5 | 20.2 | 20.9 | ||

| 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2023 | ||

| EI Operating Account annual balance2 | 3.6 | 3.4 | 3.8 | -1.1 | -1.0 | -0.8 | -0.4 | |

| EI Operating Account cumulative balance2 | -1.6 | 1.8 | 5.5 | 4.4 | 3.4 | 2.6 | 0.23 | |

| Reference: | ||||||||

| Projected premium rate (per $100 of insurable earnings) |

1.88 | 1.88 | 1.88 | 1.49 | 1.49 | 1.49 | ||

The EI Operating Account reached a cumulative deficit of $9.2 billion in 2011, due to the impact of the global recession. Since then, the EI Operating Account has been recording annual surpluses which will eventually eliminate the cumulative deficit, consistent with the principle of breaking even over time. With continued growth in EI premium revenues, annual surpluses are also expected for 2014 and 2015. As a result, the EI Operating Account is expected to return to cumulative balance in 2015.

The accumulated surplus will be gradually eliminated after the introduction of the seven-year break-even rate mechanism in 2017, resulting in a significant reduction in the premium rate that year. This new rate-setting mechanism will ensure that EI premiums are no higher than needed to pay for the EI program over time. The seven-year break-even rate will be set by the Canada Employment Insurance Commission, based on the projections of the EI Chief Actuary.

Other revenues include revenues from consolidated Crown corporations, net income from enterprise Crown corporations, returns on investments, foreign exchange revenues and proceeds from the sales of goods and services. These revenues are generally volatile, owing principally to the impact of interest rates on returns on investments and the assets in the Exchange Fund Account, and the net gains or losses from enterprise Crown corporations. These revenues are also affected by the impact of exchange rate movements on the Canadian-dollar value of foreign-denominated assets as well as flow-through items that give rise to an offsetting expense and therefore do not impact the budgetary balance.

For 2014–15, other revenues are projected to increase by 3.0 per cent based on year-to-date results. Growth in other revenues is expected to average 4.9 per cent over the remainder of the forecast horizon, primarily based on the projected profiles of interest rates and nominal GDP.

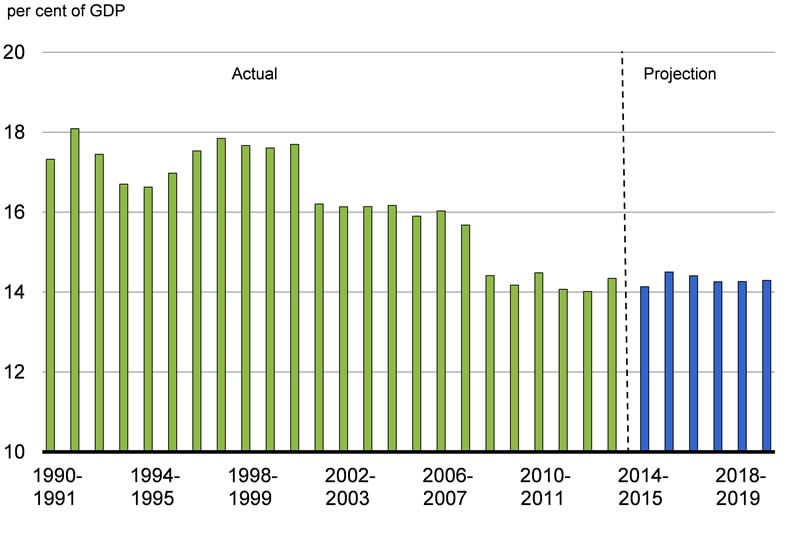

The revenue-to-GDP ratio is now at its lowest level in half a century, averaging just over 14 per cent since 2008–09 (Chart 5.2.3). This decline is due primarily to tax reduction measures. Over the forecast horizon, the revenue-to-GDP ratio is projected to remain relatively stable around its 2013–14 level.

Outlook for Program Expenses

| Projection | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2013– 2014 | 2014– 2015 | 2015– 2016 | 2016– 2017 | 2017– 2018 | 2018– 2019 | 2019– 2020 | |

| Major transfers to persons | |||||||

| Elderly benefits | 41.8 | 43.7 | 45.7 | 48.1 | 50.8 | 53.6 | 56.5 |

| Employment Insurance benefits1 | 17.3 | 17.8 | 18.4 | 19.0 | 19.5 | 20.2 | 20.9 |

| Children’s benefits | 13.1 | 14.2 | 18.0 | 18.0 | 18.3 | 18.5 | 18.7 |

| Total | 72.2 | 75.7 | 82.0 | 85.2 | 88.6 | 92.3 | 96.1 |

| Major transfers to other levels of government | |||||||

| Canada Health Transfer | 30.3 | 32.1 | 34.0 | 36.1 | 37.4 | 39.1 | 40.9 |

| Canada Social Transfer | 12.2 | 12.6 | 13.0 | 13.3 | 13.7 | 14.2 | 14.6 |

| Equalization | 16.1 | 16.7 | 17.3 | 18.0 | 18.6 | 19.5 | 20.4 |

| Territorial Formula Financing | 3.3 | 3.5 | 3.6 | 3.6 | 3.7 | 3.8 | 3.9 |

| Gas Tax Fund2 | 2.1 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.1 | 2.1 | 2.2 | 2.2 |

| Other fiscal arrangements3 | -3.5 | -4.0 | -4.5 | -4.8 | -5.1 | -5.3 | -5.6 |

| Total | 60.5 | 62.8 | 65.4 | 68.3 | 70.5 | 73.5 | 76.3 |

| Direct program expenses | |||||||

| Operating expenses | 74.7 | 74.9 | 76.1 | 78.3 | 80.2 | 82.5 | 84.3 |

| Transfer payments | 36.7 | 36.0 | 34.0 | 36.7 | 37.3 | 38.3 | 39.1 |

| Capital amortization | 4.5 | 5.2 | 5.7 | 5.8 | 6.0 | 6.4 | 6.7 |

| Total | 115.9 | 116.1 | 115.8 | 120.8 | 123.5 | 127.2 | 130.1 |

| Total program expenses | 248.6 | 254.6 | 263.2 | 274.3 | 282.7 | 293.0 | 302.6 |

| Per cent of GDP | |||||||

| Major transfers to persons | 3.8 | 3.8 | 4.1 | 4.1 | 4.0 | 4.0 | 4.0 |

| Major transfers to other levels of government | 3.2 | 3.2 | 3.3 | 3.3 | 3.2 | 3.2 | 3.2 |

| Direct program expenses | 6.1 | 5.9 | 5.8 | 5.8 | 5.6 | 5.6 | 5.5 |

| Total program expenses | 13.1 | 12.9 | 13.2 | 13.1 | 12.9 | 12.8 | 12.7 |

Table 5.2.6 provides an overview of the projections for program expenses by major component, including the measures announced in Economic Action Plan 2015. Program expenses consist of major transfers to persons, major transfers to other levels of government and direct program expenses.

Major transfers to persons increase steadily over the forecast horizon, with spending expected to increase from $75.7 billion in 2014–15 to $96.1 billion in 2019–20. Major transfers to persons consist of elderly, EI and children’s benefits.

Elderly benefits are comprised of Old Age Security, Guaranteed Income Supplement and Allowance payments to qualifying seniors, with Old Age Security payments representing approximately 75 per cent of these expenditures. The Government will spend an extra $36.5 billion on benefits for seniors over the next five years. Elderly benefits are projected to grow from $43.7 billion in 2014–15 to $56.5 billion in

2019–20, or approximately 5.3 per cent per year—faster than nominal GDP, which is projected to grow on average by 3.9 per cent per year. This increase is due to consumer price inflation, to which benefits are fully indexed, and a projected increase in the seniors’ population from 5.6 million in 2014–15 to 6.6 million in 2019–20, an average increase of 3.5 per cent per year.

The Government will spend an additional $9.0 billion on EI benefits over the next five years. EI benefits are projected to increase by 2.9 per cent to $17.8 billion in 2014–15 based on year-to-date results. Over the remainder of the projection period, EI benefits are projected to grow moderately, averaging 3.3 per cent annually, despite the projected reduction in the number of unemployed. This reflects the expectation that the share of unemployed who receive EI benefits will trend upwards and that average benefits paid to EI recipients will continue to increase based on growth in average earnings.

Children’s benefits, which consist of the Canada Child Tax Benefit and the Universal Child Care Benefit, are projected to increase over the forecast horizon, with increased spending of $20.3 billion over the next five years. This reflects growth in the eligible population, adjustments for inflation and, most importantly, the enhanced Universal Child Care Benefit (UCCB). As announced by the Government on October 30, 2014, the enhanced UCCB will provide an increased benefit of $160 per month for children under the age of 6, and a new benefit of $60 per month for children aged 6 through 17, effective January 1, 2015.

Major transfers to other levels of government are expected to increase over the forecast horizon, from $62.8 billion in 2014–15 to $76.3 billion in 2019–20.

Major transfers to other levels of government include transfers in support of health and social programs, Equalization and Territorial Formula Financing, and the Gas Tax Fund, among others.

The Government will spend an additional $26.9 billion over the next five years on the Canada Health Transfer (CHT), which is projected to grow from $32.1 billion in 2014–15 to $40.9 billion in 2019–20. Starting in 2017–18, the CHT will grow in line with a three-year moving average of nominal GDP growth, with funding guaranteed to increase by at least 3 per cent per year.

The Canada Social Transfer will continue to grow at 3 per cent per year, meaning additional spending of $5.9 billion over the next five years. The Gas Tax Fund is projected to grow from $2.0 billion in 2014–15 to $2.2 billion in 2019–20 as, starting in 2014–15, these payments are indexed at 2 per cent per year, with increases applied in $100 million increments.

The Government is committed to controlling the spending of federal departments. In fact, direct program expenses have fallen over the last four years, decreasing from $122.8 billion in 2009–10 to $115.9 billion in 2013–14. Moreover, direct program expenses for 2017–18 are expected to remain broadly in line with expenses in 2009–10. Over the forecast horizon, direct program expenses are expected to decrease as a percentage of GDP, reaching a low of 5.5 per cent of GDP in 2019–20, well below pre-recession levels.

Direct program expenses include operating expenses, transfer payments administered by departments and capital amortization.

Operating expenses reflect the cost of doing business for more than 100 government departments and agencies. The current projection reflects savings from the operating budget freeze, which is in place for 2014–15 and 2015–16. Operating expenses are growing modestly over the forecast horizon, with spending increasing from $74.7 billion in 2013–14 to $84.3 billion in 2019–20. However, as a share of GDP, operating expenses decline over the projection period from 3.9 per cent in 2013–14 to 3.5 per cent in 2019–20.

Transfer payments administered by departments are broadly stable over the forecast horizon, decreasing from $36.7 billion in 2013–14 to $34.0 billion in 2015–16, then increasing to $39.1 billion in 2019–20. The decrease in the early years of the forecast is largely the result of temporary, one-time costs in 2013–14 associated with federal disaster assistance for the flooding in Alberta.

Amounts for capital expenses are presented on an accrual basis. The amount of capital amortization is expected to increase modestly from $4.5 billion in 2013–14 to $6.7 billion in 2019–20 as a result of new investments and upgrades to existing capital.

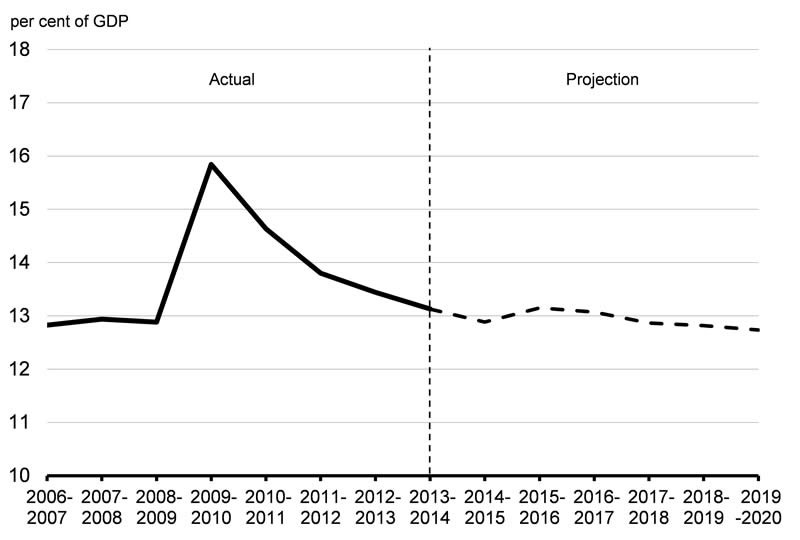

As a share of GDP, program expenses are projected to decline from 13.1 per cent in 2013–14 to 12.7 per cent in 2019–20, which is below its pre-recession level (Chart 5.2.4).

Financial Source/Requirement

The budgetary balance is presented on a full accrual basis of accounting, recording government revenues and expenses when they are earned or incurred, regardless of when the cash is received or paid.

In contrast, the financial source/requirement measures the difference between cash coming in to the Government and cash going out. This measure is affected not only by the budgetary balance but also by the Government’s non-budgetary transactions. These include changes in federal employee pension accounts; changes in non-financial assets; investing activities through loans, investments and advances; and changes in other financial assets and liabilities, including foreign exchange activities.

| Projection | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2013–2014 | 2014–2015 | 2015–2016 | 2016–2017 | 2017–2018 | 2018–2019 | 2019–2020 | |

| Budgetary balance | -5.2 | -2.0 | 1.4 | 1.7 | 2.6 | 2.6 | 4.8 |

| Non-budgetary transactions | |||||||

| Pensions and other accounts | 5.4 | 4.0 | 0.2 | -0.6 | -1.9 | -1.4 | -1.4 |

| Non-financial assets | -1.5 | -2.2 | -2.4 | -3.1 | -2.0 | -1.7 | -1.6 |

| Loans, investments and advances | |||||||

| Enterprise Crown corporations | -2.4 | -5.2 | -4.7 | -5.0 | -5.7 | -6.0 | -6.0 |

| Insured Mortgage Purchase Program | 42.0 | 9.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Other | 0.3 | -1.0 | -2.8 | -0.6 | -1.0 | -1.0 | -0.8 |

| Total | 39.9 | 3.8 | -7.5 | -5.7 | -6.7 | -7.0 | -6.8 |

| Other transactions | -21.2 | -10.3 | -6.0 | -5.2 | -7.9 | -4.1 | -6.2 |

| Total | 22.7 | -4.7 | -15.8 | -14.6 | -18.5 | -14.2 | -16.0 |

| Financial source/requirement | 17.5 | -6.7 | -14.4 | -12.8 | -15.9 | -11.6 | -11.2 |

As shown in Table 5.2.7, a financial requirement is projected over the entire forecast period. The projected financial requirements for 2015–16 to 2019–20 largely reflect requirements associated with the acquisition of non-financial assets, increases in retained earnings of enterprise Crown corporations and growth in other assets, including financing of the Exchange Fund Account.

A financial source is projected for pensions and other accounts for 2015–16, changing to a financial requirement for 2016–17 to 2019–20. Pensions and other accounts include the activities of the Government of Canada’s employee pension plans, as well as those of federally appointed judges and Members of Parliament, as well as a variety of future benefit plans, such as health care and dental plans and disability and other benefits for war veterans and others. The financial source and requirements for pensions and other accounts reflect adjustments for pension expenses not funded in the period, as well as cash outlays for benefit payments and investments in pension assets.

Financial requirements for non-financial assets mainly reflect the difference between cash outlays for the acquisition of new tangible capital assets and the amortization of capital assets included in the budgetary balance. They also include disposals of tangible capital assets and changes in inventories and prepaid expenses. A net cash requirement of $2.4 billion is estimated for 2015–16.

Loans, investments and advances include the Government’s investments in enterprise Crown corporations, such as Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation (CMHC), Export Development Canada, the Business Development Bank of Canada (BDC) and Farm Credit Canada (FCC). They also include loans, investments and advances to national and provincial governments and international organizations, and for government programs. The requirements for enterprise Crown corporations projected from 2015–16 to 2019–20 reflect retained earnings of enterprise Crown corporations as well as the Government’s decision in Budget 2007 to meet all the borrowing needs of CMHC, BDC and FCC through its own domestic debt issuance. The financial source in 2014–15 under the Insured Mortgage Purchase Program is due to the winding down in March 2010 of purchases of insured mortgage pools under the plan and the subsequent repayments of principal as the assets under the plan mature. In general, loans, investments and advances are expected to generate additional revenues for the Government in the form of interest or additional net profits of enterprise Crown corporations, which largely offset debt charges associated with these borrowing requirements. These revenues are reflected in projections of the budgetary balance.

Other transactions include the payment of tax refunds and other accounts payable, the collection of taxes and other accounts receivable, the conversion of other accrual adjustments included in the budgetary balance into cash, as well as foreign exchange activities. Projected cash requirements associated with other transactions reflect forecast increases in the Government’s official international reserves held in the Exchange Fund Account, as per the prudential liquidity plan, as well as expected growth in the Government’s balance of taxes receivable, net of amounts owing to taxpayers, in line with the historical trend.

Risks to the Fiscal Projections

Risks associated with the economic outlook are the greatest source of uncertainty to the fiscal projections. To help quantify these risks in respect of their impact on the fiscal outlook, tables illustrating the sensitivity of the budgetary balance to a number of economic shocks are provided below.

Besides the economic outlook, there are other unique sources of upside or downside risks to the fiscal projections, such as the volatility in the relationships between fiscal variables and the underlying activities to which they relate. For example, relationships between personal income taxes and personal income or the extent to which departments and agencies do not fully use all of the resources appropriated by Parliament can fluctuate for reasons not directly linked to economic variables. These fluctuations introduce an additional level of uncertainty to the fiscal projections.

Sensitivity of the Budgetary Balance to Economic Shocks

Changes in economic assumptions affect the projections for revenues and expenses. The following tables illustrate the sensitivity of the budgetary balance to a number of economic shocks:

- A one-year, 1-percentage-point decrease in real GDP growth driven equally by lower productivity and employment growth.

- A decrease in nominal GDP growth resulting solely from a one-year,

1-percentage-point decrease in the rate of GDP inflation (assuming that the Consumer Price Index moves in line with GDP inflation). - A sustained 100-basis-point increase in all interest rates.

These sensitivities are generalized rules of thumb that assume any decrease in economic activity is proportional across income and expenditure components, and are meant to provide a broad illustration of the impact of economic shocks on the outlook for the budgetary balance. Actual economic shocks may have different fiscal impacts. For example, they may be concentrated in specific sectors of the economy or cause different responses in key economic variables (e.g. GDP inflation and Consumer Price Index inflation may have different responses to a given shock).

| Year 1 | Year 2 | Year 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Federal revenues | |||

| Tax revenues | |||

| Personal income tax | -2.6 | -2.7 | -3.1 |

| Corporate income tax | -0.3 | -0.4 | -0.4 |

| Goods and Services Tax | -0.3 | -0.3 | -0.3 |

| Other | 0.0 | -0.2 | -0.2 |

| Total tax revenues | -3.2 | -3.6 | -4.1 |

| Employment Insurance premiums | -0.2 | -0.2 | -0.2 |

| Other revenues | -0.1 | -0.1 | -0.1 |

| Total budgetary revenues | -3.4 | -3.9 | -4.4 |

| Federal expenses | |||

| Major transfers to persons | |||

| Elderly benefits | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Employment Insurance benefits | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.5 |

| Children’s benefits | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 |

| Total | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.5 |

| Other program expenses | -0.2 | -0.1 | -0.3 |

| Public debt charges | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.6 |

| Total expenses | 0.7 | 0.8 | 0.8 |

| Budgetary balance | -4.1 | -4.7 | -5.2 |

A 1-percentage-point decrease in real GDP growth proportional across income and expenditure components reduces the budgetary balance by $4.1 billion in the first year, $4.7 billion in the second year and $5.2 billion in the fifth year (Table 5.2.8).

- Tax revenues from all sources fall by a total of $3.2 billion in the first year and by $3.6 billion in the second year. Personal income tax revenues decrease as employment and wages and salaries fall. Corporate income tax revenues fall as output and profits decrease. GST revenues decrease as a result of lower consumer spending associated with the fall in employment and personal income.

- EI premium revenues decrease as employment and wages and salaries fall. In order to isolate the direct impact of the economic shock and provide a general overview of the fiscal impacts, the EI premium revenue impacts do not include changes in the premium rate.

- Expenses rise, mainly reflecting higher EI benefits (due to an increase in the number of unemployed) and higher public debt charges (reflecting a higher stock of debt due to the lower budgetary balance). This rise is partially offset by lower other program expenses (as certain programs are tied directly to growth in nominal GDP).

| Year 1 | Year 2 | Year 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Federal revenues | |||

| Tax revenues | |||

| Personal income tax | -2.3 | -1.6 | -1.5 |

| Corporate income tax | -0.3 | -0.4 | -0.4 |

| Goods and Services Tax | -0.3 | -0.3 | -0.3 |

| Other | -0.2 | -0.2 | -0.2 |

| Total tax revenues | -3.1 | -2.4 | -2.5 |

| Employment Insurance premiums | -0.1 | -0.2 | -0.2 |

| Other revenues | -0.1 | -0.1 | -0.1 |

| Total budgetary revenues | -3.3 | -2.7 | -2.8 |

| Federal expenses | |||

| Major transfers to persons | |||

| Elderly benefits | -0.4 | -0.5 | -0.6 |

| Employment Insurance benefits | -0.1 | -0.1 | -0.1 |

| Children’s benefits | 0.0 | -0.1 | -0.1 |

| Total | -0.5 | -0.6 | -0.8 |

| Other program expenses | -0.4 | -0.4 | -1.0 |

| Public debt charges | -0.5 | 0.1 | 0.4 |

| Total expenses | -1.4 | -1.0 | -1.3 |

| Budgetary balance | -1.9 | -1.7 | -1.5 |

A 1-percentage-point decrease in nominal GDP growth proportional across income and expenditure components resulting solely from lower GDP inflation (assuming that the Consumer Price Index moves in line with GDP inflation) lowers the budgetary balance by $1.9 billion in the first year, $1.7 billion in the second year and $1.5 billion in the fifth year (Table 5.2.9).

- Lower prices result in lower nominal income and, as a result, personal income tax revenues decrease, reflecting declines in the underlying nominal tax base. As the parameters of the personal income tax system are indexed to inflation and automatically adjust in response to the shock, the fiscal impact is smaller than under the real shock. For the other sources of tax revenue, the negative impacts are similar under the real and nominal GDP shocks.

- EI premium revenues decrease in response to lower earnings. In order to isolate the direct impact of the economic shock and provide a general overview of the fiscal impacts, the EI premium revenue impacts do not include changes in the premium rate.

- Other revenues decline slightly as lower prices lead to lower revenues from the sales of goods and services.

- Partly offsetting lower revenues are the declines in the cost of statutory programs that are indexed to inflation, such as elderly benefit payments and the Canada Child Tax Benefit, and downward pressure on federal program expenses. Payments under these programs are smaller if inflation is lower. In addition, other program expenses are also lower as certain programs are tied directly to growth in nominal GDP.

- Public debt charges decline in the first year due to lower costs associated with Real Return Bonds, then rise due to the higher stock of debt.

| Year 1 | Year 2 | Year 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Federal revenues | 1.2 | 1.6 | 2.4 |

| Federal expenses | 1.7 | 2.8 | 4.4 |

| Budgetary balance | -0.5 | -1.2 | -2.0 |

An increase in interest rates decreases the budgetary balance by $0.5 billion in the first year, $1.2 billion in the second year and $2.0 billion in the fifth year (Table 5.2.10). The decline stems entirely from increased expenses associated with public debt charges. The impact on debt charges rises through time as longer-term debt matures and is refinanced at higher rates. Moderating the overall impact is an increase in revenues associated with the increase in the rate of return on the Government’s interest-bearing assets, which are recorded as part of other revenues. The impacts of changes in interest rates on public sector pension and benefit expenses are excluded from the sensitivity analysis.